Back to Adak

US defense officials say they support reopening a remote Cold War-era base in Alaska to help keep track of Russian and Chinese activity around the Arctic.

BANGKOK — Three decades after being shuttered, the US military base on Adak in Alaska’s Aleutian Islands may soon be back in action, as Pentagon tries to bolster its presence in the Arctic and Northern Pacific.

US forces have returned to WWII-era outposts in the Western Pacific in recent years to counter China’s growing military reach and influence there. US officials have also devoted more attention to the Arctic as climate change has made it more accessible for military and commercial activity. Their growing focus on Alaska reflects renewed appreciation for its value as a gateway between the Pacific and Arctic oceans and an outpost from which to deploy forces into Asia and Europe.

The US is not alone in its interest. Russia, which is building up its own military presence in the Arctic, has done air and naval patrols around its Far East and Alaska more frequently since the late 2000s. China, which deems itself a “near-Arctic” state, has done regular naval patrols near the Aleutians over the past decade; in September its coast guard said it had sailed into the Arctic Ocean for the first time. The two countries have also displayed their expanding military cooperation in the region, with joint naval patrols and their first joint bomber patrol near Alaska in July 2024.

Encounters with those forces have generally been professional, but US officials see their activity as provocative and say greater presence in Alaska — especially at Adak, the reopening of which has been discussed for years — as a way to counter it. “You have Chinese and Russians coming into our [air-defense identification zone] with ships and aircraft. You could launch from Adak, get right behind them. You could be flanking China. That is a really strategic” base, Sen. Dan Sullivan of Alaska said in December.

Sullivan, a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, has for years advocated military investment in Alaska and often presses military and defense officials to visit the state and acknowledge its importance. At hearings this year, Sullivan has asked top officials to support forces and infrastructure there.

In April, Sullivan asked Adm. Samuel Paparo, the head of US Indo-Pacific Command, to reiterate the support for returning to Adak that Paparo had expressed in a classified hearing. “We should reopen Adak, and we should enhance the ability to operate out of Eareckson,” Paparo responded, referring to an Air Force base on Shemya Island at the western edge of the Aleutians — closer to Russia than the US mainland — that has an airfield and missile-defense radars.

Adak, about 1,200 miles southwest of Anchorage, “is a further western point” that would, along with Eareckson, enable US forces “to gain time and distance on any force” trying “to penetrate” around Alaska and would enable up to 10 times “the maritime patrol reconnaissance aircraft coverage of that key and increasingly contested space,” Paparo said.

Paparo echoed his counterpart at US Northern Command, Gen. Gregory Guillot, who backed reopening Adak when asked by Sullivan at a hearing in mid-February.

“I would support Adak for sure, for maritime and air access,” Guillot said. Guillot, who also commands NORAD, said pilots at bases in central and southern Alaska have to fly “a thousand miles or more” over harsh terrain “usually at night” to intercept aircraft in the ADIZ, which is not territorial airspace but is closely monitored. Having “forward points” in Alaska would “allow us to pre-position search-and-rescue aircraft or be able to land there in an emergency, which are capabilities that we just don't have right now,” Guillot added.

Later in February, Sullivan asked John Phelan, nominee to be secretary of the Navy, about reopening Adak, which Phelan said “is worth looking at” and that if confirmed he intended “to work with you on it and also talk with the combatant commanders, particularly Adm. Paparo.”

Front line in the high north

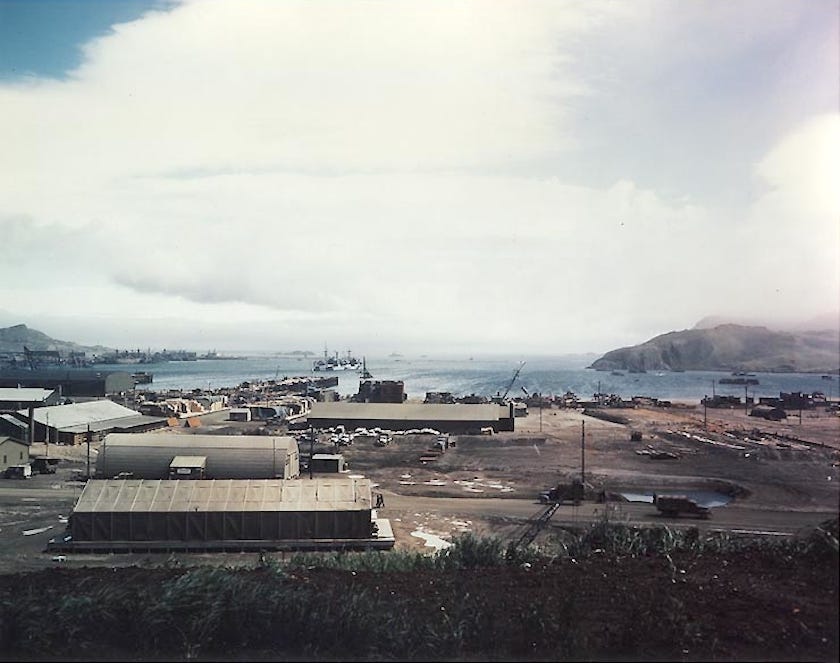

The US acquired Adak when it bought Alaska from Russia in 1867, but there was no military presence there until 1942, when troops arrived to support the recapture of Attu and Kiska, islands to the west that the Japanese had occupied. The Air Force operated the base after WWII, but the Navy took over in 1950. It ultimately covered most of the northern part of the island and was home to several thousand troops for most of the Cold War.

The Adak naval base hosted P-3 patrol planes that scoured the area for Soviet naval forces and supported other military operations. It also housed intelligence-gathering facilities, including a Sound Surveillance System terminal for monitoring Soviet submarine activity, as well as nuclear depth charges designed to blast those Soviet subs out of the water. Eareckson Air Station on Shemya Island also supported bomber and reconnaissance patrols and hosted radars to track Soviet missile launches.

Operations at Adak wound down after the Soviet collapse and ceased in 1997, but the base can still support military activity. “It has three piers, two 8,000-foot runways, a big hangar, 22 million gallons of fuel storage — one of the biggest fuel-storage depots anywhere on the planet,” Sullivan said at the hearing in April.

Past inquiries about reopening Adak found it would be prohibitively expensive, but Sullivan said at the April hearing that officials from the Navy, the state of Alaska, and the Aleut Corporation, a native group that manages much of the island, had recently done a site assessment and that US Northern Command was preparing a report on reopening scenarios with “low, medium, to high” levels of operation.

While Adak’s future is uncertain, the military has been expanding and enhancing its presence elsewhere in Alaska so it can do more training in the Arctic and supplement its posture in the Indo-Pacific. The Air Force has stationed more than 100 stealth jets in Alaska — the most in any state and the “preponderance” of Indo-Pacific Command’s fifth-generation fighters, Paparo said in April — and those jets have deployed as far as Singapore for exercises. The Army has reorganized Alaska-based paratroopers into an airborne division focused on training for major combat operations. Those soldiers have also shown their reach, launching from Alaska for training jumps in Guam in 2020 and in Norway in 2024.

US troops have also ventured back to Adak and other Alaskan islands, including Shemya, for training. That will continue this summer during the Northern Edge exercise. The Air Force plans to use Adak to train for agile combat employment, or ACE, in which forces disperse from main bases to distant outposts to sustain operations when main bases are attacked. ACE is “the means by which we achieve more dynamism among the force,” Paparo said at the April hearing.

President Donald Trump and other officials have pledged more defense investment for Alaska, but efforts to increase military capability there face a number of challenges. Work on a deepwater port in Nome — the US’s first in the Arctic — has been delayed by cost concerns. Rising temperatures also undermine military and civilian infrastructure, though the Trump administration and the Pentagon have dismissed efforts to address climate change.

While military activity in the Arctic gets much of the attention, US and Western officials also warn that China is using diplomatic, commercial, and scientific initiatives to make inroads there that could give it strategic advantages. At the April hearing, Sullivan said a Chinese shipping firm he suspected was “a front company” for China’s military has been asking the Aleut Corporation “once a year” about leasing Adak.