The US is trying to end its 'drought' in Cambodia

A flurry of official visits, including the first by a US Navy ship in eight years, shows Washington is trying to mend fences in Southeast Asia.

BANGKOK — When USS Germantown pulled into the port of Sihanoukville on October 16, 2016, the military relationship between the US and Cambodia appeared strong.

They had held their Angkor Sentinel bilateral exercise that March and were already planning the 2017 version. They were also gearing up for their Cooperation Afloat Readiness and Training maritime exercise, which began at Cambodia’s Ream naval base two weeks later. Both exercises had been held annually since 2010, and the countries had other ongoing military exchanges, such as a humanitarian assistance mission led by US Navy engineers who deployed to Cambodia each year.

Within a few weeks of Germantown’s arrival, however, there were signs of a major shift. In mid-December, Cambodia and China held their first Golden Dragon military exercise, which Beijing said aimed to "deepen pragmatic cooperation and enhance the friendship.” In mid-January 2017, Cambodia told the US it would “postpone” Angkor Sentinel that year and in 2018. The CARAT drill was suspended too, and in late March, the US Embassy said Cambodia had ended the US Navy engineer program after nine years. Phnom Penh offered few convincing explanations for those decisions.

For the US, that was all evidence of a troubling reversal: Cambodia, bridling at American criticism of its democratic and human-rights records, was freezing out Washington and embracing Beijing, which had nurtured its relationship with Phnom Penh through diplomatic engagement and heavy investment and built defense ties with military aid and arms sales.

The rifts weren’t new. “Since 2008 or 2009, Cambodia's defense relations with the US has gone from bad to worse, and the Americans actually did not provide much assistance to the Cambodians after that. The Chinese came in and said, Look, do you need trucks? Do you need equipment?” Rahman Yaacob, a research fellow at Australia’s Lowy Institute, said on a recent episode of the institute’s podcast.

Cambodia continued its military exchanges with China while it froze out the US. Golden Dragon took place every year except for 2021 and 2022 and grew each time, but the US’s biggest concern has been developments at Ream naval base.

In late 2018, Cambodia’s longtime leader, Hun Sen, said Vice President Mike Pence had sent him a letter “addressing concern that Cambodia allows a navy base for China in the future.” Several months after that, a US defense official wrote to Cambodia’s government to ask why it had declined a US offer to repair US-funded facilities at Ream. A few weeks later, The Wall Street Journal, citing “US and allied officials,” reported that Cambodia had signed a secret deal allowing China’s navy to use the base.

Work at Ream, including demolition of US-funded buildings, continued in 2020 and 2021, and foreign visitors, including US officials, got only limited access to the base or were outright denied. In June 2022, Chinese and Cambodian officials broke ground on the base’s Chinese-funded “modernization.” Among the facilities built there since then is a 1,000-foot pier, where two Chinese corvettes docked in December and remained for much of the first half of 2024. In May, those warships and other Chinese forces took part in the largest Golden Dragon yet.

China’s navy swapped the corvettes for another pair in mid-2024, and the vessels continue to train with Cambodian forces. Beijing has said it will give those ships to Cambodia. “To my understanding, they will be given to the Cambodians free of charge,” Yaacob said.

‘A seven-year drought'

With bilateral exercises and other military cooperation suspended, Washington continued to punish Cambodia’s government for undermining democracy, human-rights abuses, corruption, and links to China.

In 2018, the Pentagon suspended its International Military Education and Training programs in Cambodia, and in 2021 it ended a program sponsoring Cambodian students at US military academies because of “weak cooperation” by Phnom Penh. That same year, the Commerce and State departments limited Cambodia’s access to military and military-related items. The US sanctioned several Cambodia officials for corruption or rights abuses after 2018 and sanctioned several more and paused some assistance after a national election in 2023 that it deemed “neither free nor fair.”

Over the past year, however, the US has backed off its sharpest criticism and reengaged. In February, two top Defense and State department officials for the Indo-Pacific region traveled to Cambodia for meetings, including with Prime Minister Hun Manet, who took over from his father in August 2023.

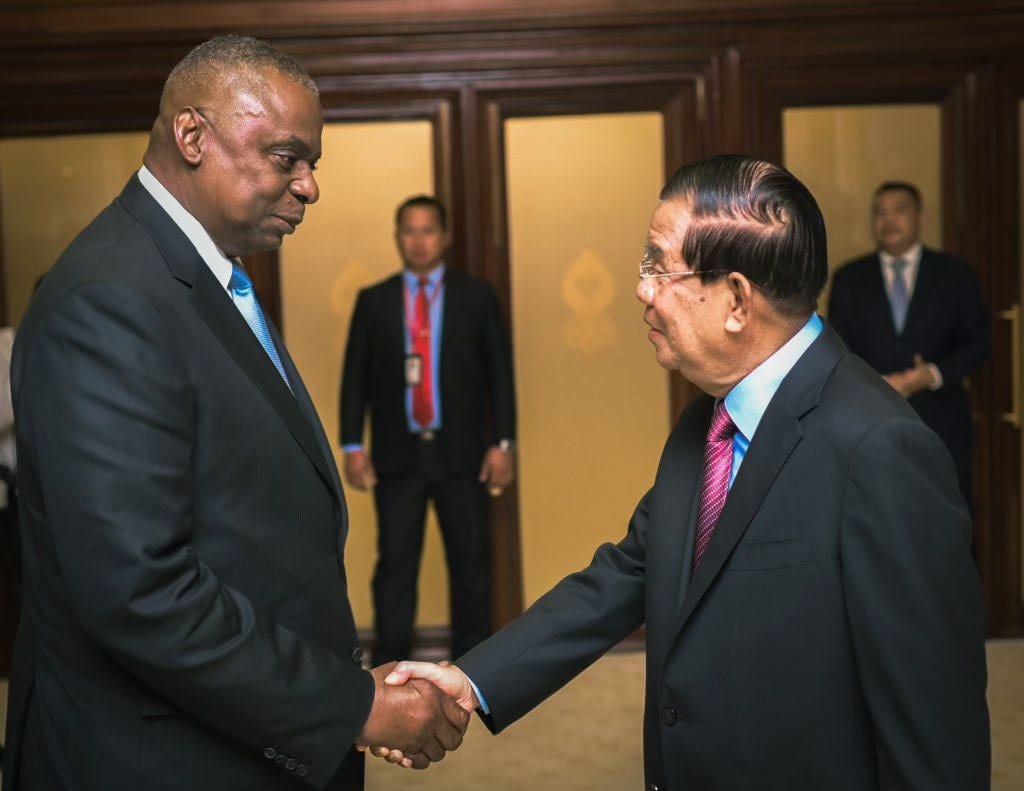

In June, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin visited Cambodia to meet with both Huns and other officials in what was the first bilateral visit by a US defense secretary. (Austin visited Cambodia and met with its defense minister in November 2022 during the annual ASEAN Defense Ministers Meeting-Plus.)

A US official said Austin’s meeting wasn’t about “significant deliverables” but did cast it as a chance to reset the relationship. Afterward, the elder Hun, who is now president of the senate, wrote on Facebook that Austin said the US wanted "to restore and improve relations,” including by reopening West Point to Cambodian personnel.

In September, a C-130J cargo plane landed in Cambodia to refuel, allowing for a brief meeting between US and Cambodian officers that marked the end of “a seven-year drought of engagements and partnerships,” the US Air Force said in a release. The following month, the deputy assistant secretary of defense for Southeast Asia visited Cambodia for the first US-Cambodia Defense Policy Dialogue held since 2019. In November, Austin again met his Cambodian counterpart during the ADMM-Plus in Laos.

US defense diplomacy ended the year on a high note, when USS Savannah arrived in Sihanoukville on December 16 for “a goodwill visit that will boost US-Cambodia coordination,” the US Embassy said. It was the first visit by a US Navy ship in eight years, and it coincided with a visit by Adm. Samuel Paparo, the head of US Indo-Pacific Command, who met with Hun Manet and Cambodian defense officials with whom Paparo discussed "confidence-building measures” for the bilateral relationship and “rebuilding bilateral defense and security cooperation.”

Paparo also “engaged with” the Ream naval base commander when the latter visited Sihanoukville to tour USS Savannah. A day later Paparo met with Cambodia’s defense minister “to discuss military cooperation and exchanges” while they were both in Vietnam for an arms show.

Power struggle

US and Chinese engagement with Cambodia reflects both countries’ broader interests in Southeast Asia. Beijing already has close cultural, diplomatic, and economic ties with the region and wants to deepen its security relationships — at the US’s expense.

“Senior Cambodian officials inform me that the Chinese, they are not happy about ASEAN because the largest ASEAN trading partner is China and yet some ASEAN member-states prefer the Americans as a security partner,” Yaacob said, referring to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. “Beijing's objective is to replace the Americans' influence in the defense area in Southeast Asia, so they are hoping that by providing military assistance to the Cambodians, it will demonstrate that they are more of a reliable security partner.”

Experts say Washington is losing influence in Southeast Asia because of ire over its foreign policy (especially in the Middle East), disinterest in its limited economic outreach, and wariness about being made to side against China, but the US still has extensive economic ties in the region and is considered by many there to be the military partner of choice. US defense diplomacy with Cambodia mirrors efforts in the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, and elsewhere in the region this year.

When asked about their conversations with Phnom Penh, US officials acknowledge they have talked about Ream and China’s role there but stress that they are focused on discussing ways to “strengthen” US-Cambodian defense ties and want “continued dialogue.”

The ascent of Hun Manet, who was educated at West Point and NYU, has also played in a part in the renewed outreach. Hun is seen by some as leading a new generation, potentially one open to friendlier relations with the West, into power. Beijing has sought to underscore its support for Cambodia with high-level engagement this year but is “concerned that Hun Manet will shift closer to the US,” Yaacob said. “They are quite uncertain about Cambodians' loyalty.”

The younger Hun has pledged to pursue an “independent” foreign policy and “building good friendships and cooperation with all countries,” but he may find limited room to maneuver. Elite networks with financial and political interests in relations with China may resist a shift away from Beijing. There also appears to “a power struggle” between the younger and older generations of leadership over defense and foreign policy, with Hun Sen “still trying to exert certain influence,” Yaacob said.

Beijing remains Phnom Penh’s main investor, creditor, and military supplier, but its falling investment and apparent backtracking on the Funan Techo canal project may hint at future limits on what China will provide. Relations with the US could also take a turn if the incoming Trump administration takes a hard line on other countries’ dealings with China.

For now, at least, the US military isn’t asking anyone to pick sides. “We are taking a wait-and-see attitude toward the PRC’s relationship at the Ream naval base, but Cambodia’s relationship with the People’s Republic of China is one that we have a respect for,” Paparo told the press in Cambodia. “So with regard to our visit and our activities with Cambodia, it’s not to counter anyone. It’s a relationship that is on its own terms.”