China shows off its newest 5th-gen jet as rivals scramble to boost their stealth fleets

Thousands of fifth-gen fighters are set to be delivered over the next decade, and many militaries are already working on sixth-generation aircraft.

Programming note: I was on the China-Global South podcast last month to discuss an article I wrote this summer on China’s new military base in Cambodia. Check it out on the China-Global South website or on Apple or Spotify.

BANGKOK — China unveiled its latest fifth-generation jet at Airshow China 2024 in mid-November, touting the newest addition to a growing stealth fleet that worries US military leaders and is driving investment in advanced aircraft across the region.

This year’s edition of the biennial airshow coincided with the 75th anniversary of China’s People’s Liberation Army Air Force, and the PLAAF again used the event to debut an aircraft: the J-35A. The jet has been in development by Shenyang Aircraft Corporation, a subsidiary of the state-owned Aviation Industry Corporation of China, for more than a decade. The earliest version, the FC-31, appeared in the early 2010s, with prototypes flying in 2012 and 2016. Later versions, sometimes called the J-31 or J-35, were thought to be for export or naval use. While the J-35A is for China’s air force, a J-35 variant is still believed to be in the works for China’s growing aircraft-carrier fleet.

With its apparent entry into service, the J-35A joins the J-20 as the PLAAF’s second stealth jet and makes China the only country with two operational fifth-generation fighters aside from the US, which has the F-22 and F-35. The J-20 appears to be larger than its counterpart and is likely focused on air-superiority missions, earning it comparisons to the F-22. The J-35A is billed as a medium-size multi-role fighter like the F-35, though it has two engines compared to the F-35’s one. Ahead of the airshow, AVIC said the J-35A’s missions would include air superiority as well as ground and maritime strikes.

A Chinese air force officer said at the airshow that test pilots found the J-35A to be “highly agile, stable, and operationally efficient” and “with excellent handling and user-friendly human-machine interaction.” Despite statements like that, little is known for sure about the J-35A’s design and capabilities. Based on what was displayed, it may have greater internal fuel capacity than previous prototypes and likely has advanced avionics, like an active electronically scanned array radar that would facilitate use of the PL-15 long-range air-to-air missile, a weapon that worries the US and its allies.

While it is visually similar to the stealthy F-35, it’s not clear if the J-35A has a radar-absorbent coating like the F-35 or communications systems and other features meant to make it harder to detect, though the jet’s sensors and materials have likely been improved over older models thanks to recent improvements in Chinese technology.

Earlier J-35 models used Russian-made engines, a result of China’s struggles to develop them, but more recent versions likely have Chinese-designed engines. An air force spokesman said at the airshow that the J-35A, “with its domestically developed engine," is “an important addition to” the PLAAF fighter fleet. While Chinese jets are being upgraded with domestically designed engines — including the J-20 and the Y-20 cargo plane — reliability issues mean they still lag Western-made engines.

China’s biggest planes are spreading their wings

China is showing off why the Y-20 is a central part of its plans to project military power across the planet

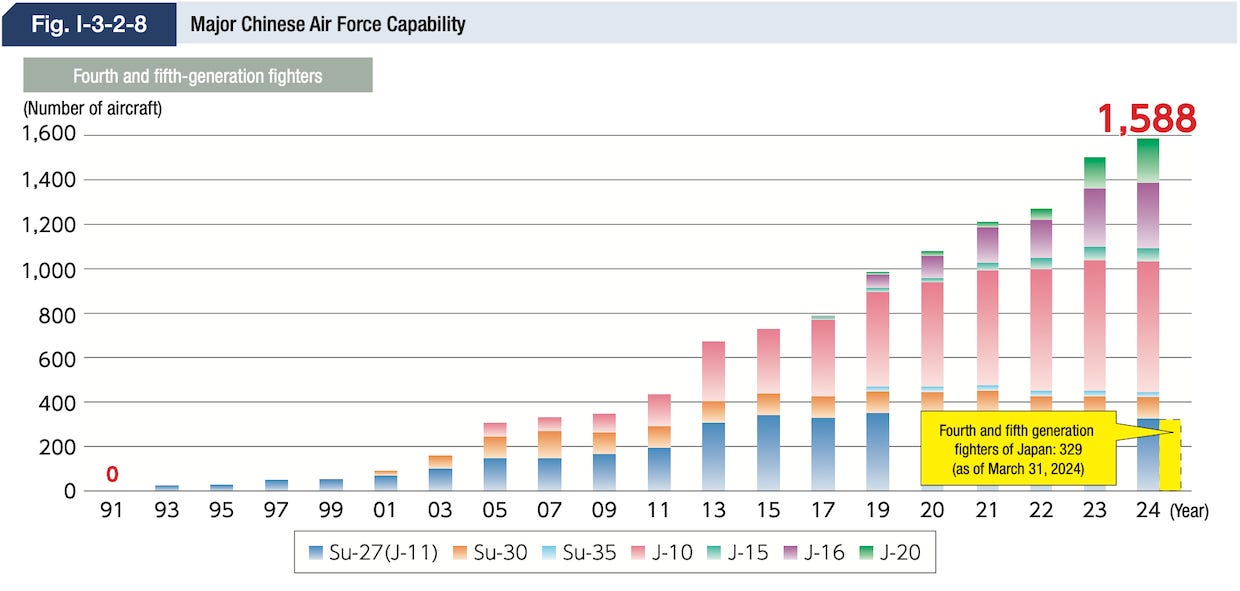

The J-35A may still be years from joining exercises and other operations, but it will bolster what is already one of the world’s largest air forces, with some 1,800 fighter jets and roughly 1,000 other combat aircraft in service, according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies’ 2024 Military Balance report. J-20s remain a small part of that force, numbering about 200 at the end of 2023, but it “is the premier combat aircraft in PLAAF service and remains the focus of incremental upgrades,” the report said.

J-20 production is also increasing. The jet was introduced in 2017 and just 40 were believed to be in service in early 2022, but deliveries picked up at the end of that year, and 70 were added between mid-2023 and mid-2024 alone, according to Janes, which said in June that about 195 J-20s were operational. Some 600 J-20s are expected to be delivered over the next decade, according to a recent forecast by Aviation Week. (The forecast also said more than 200 J-31s were to be delivered over that period, possibly referring to the naval variant.)

Alongside upgrades and expanded pilot training, the J-20 fleet’s growth allows more of them to be fielded with frontline units. According to Janes, Southern Theater Command, which is responsible for the South China Sea, had one air brigade with J-20s as of 2023 but may be adding them to two others. Eastern Theater Command, responsible for the East China Sea and the Taiwan Strait, had two brigades operating J-20s as of 2023 and appeared to start adding them to another brigade during that year. Western Theater Command, responsible for the disputed border with India, is adding J-20s to one mixed air brigade and has one dedicated J-20 air brigade that grew from at least 15 jets in 2023 to as many as 28 in 2024.

Having more J-20s means more older jets can be replaced, upgrading the overall force, and that J-20s can be used more frequently, allowing aircrews to gain experience. Gen. Kenneth Wilsbach, commander of US Pacific Air Forces from July 2020 to February 2024, said in March 2022 that Chinese pilots were handling the J-20 “pretty well,” describing an encounter over the East China Sea where F-35s got “relatively close” to J-20s and “[we] were relatively impressed with command-and-control” associated with them.

Wilsbach and other commanders play down the impact of the J-20 and the quality of the Chinese air force’s aircraft and personnel compared to those of the US, but they also warn that China is developing weapons like the J-20 as part of the largest military buildup since World War II with the goal of preventing the US from intervening in a conflict around Taiwan or elsewhere in the region.

“Today, we face a China that has been working for decades to develop and field a range of systems designed to defeat the United States in the Western Pacific. China intends to dominate in space, in cyberspace, and in the air,” Frank Kendall, the US Air Force’s top civilian official, said in a speech on November 12.

Next-gen now

Despite China’s advances, experts still consider Western fighter aircraft to be more capable, especially the F-35, which entered service with the US military in the mid-2010s. F-35 variants already comprise the world’s sixth-largest military aircraft fleet but are projected to be the second-largest by 2034, with more than 1,600 jets to be delivered between now and then, according to Aviation Week's forecast.

IISS tallies show that the US Air Force has 375 of the 1,763 F-35As it plans to buy, while the US Navy has 68 of the 273 F-35Cs it expects to order for use aboard its carriers. The US Marine Corps plans to buy 67 F-35Cs and 353 F-35Bs to use aboard amphibious ships and has received 15 and 148 of them, respectively.

Aviation Week also projected that nearly half of F-35 deliveries by value over the coming decade will go to US allies, and allies near China are some of the top buyers. Japan, the biggest foreign F-35 buyer, has received 37 of 105 F-35As and may purchase as many as 42 F-35Bs. Australia has received 63 of 100 F-35As it plans to order, and South Korea has gotten 40 of the 60 F-35As it expects to buy. Singapore, which is not a formal ally but works closely with the US military, plans to order 12 F-35Bs and eight F-35As.

The F-35 program is nearly two decades old but still struggles with tech upgrades and deficiencies that raise doubts about the jet’s combat readiness. Even with those issues, officials tout the benefits of fielding more F-35s, especially increased opportunities for training that replicates threats they expect to face from Russia and China.

“Despite the challenges that that program may have had, the fact that it continues to deliver and put airplanes not only in the United States Air Force and the United States military but into partner militaries as well” makes the F-35 “probably the greatest platform” for building “interoperability and interchangeability” among those forces, Gen. Kevin Schneider, the current commander of US Pacific Air Forces, told me in an interview in July.

As fifth-gen jets are still being built and delivered, militaries are already looking to the next generation. Russian and Chinese officials say they have programs underway, but details about each are sketchy. The US Air Force has paused its Next-Generation Air Dominance program to assess potential designs and cost, but France, Germany, and Spain are ironing out issues in their Future Combat Aircraft System program, which aims to deliver an aircraft by 2040, and the UK, Italy, and Japan recently agreed to accelerate their Global Combat Air Program, which aims to deploy an aircraft by 2035.

Operating fifth-generation fleets while developing sixth-generation aircraft will be a headache for many of those countries, but defense officials say the projects are needed to maintain their military edge.

Work on the F-35, “although it has some challenges right now, will see the jet continue to overmatch our adversaries well into the future,” British Air Chief Marshal Sir Richard Knighton, chief of the Air Staff, said in a speech on November 11.

“But the proliferation of stealth capability through the likes of the Chinese J-20 and Russian Su-57, as well as increasingly long-range air-to-air weapons like the PL-15 Thunderbolt, mean that we also need to be planning for the next-generation capabilities now,” Knighton added. “That is why we need GCAP. GCAP is very deliberately being designed to complement and enhance the capabilities of F-35, not replace it.”